Figure 1. I thought this looked like ChatGPT attempting to implement AES-CBC, but turns out this is PCBC mode

I rolled my own crypto. What could go wrong? (code)

Before breaking the program, I try to understand how it works exactly. After all, being good at crypto requires the ability to comprehend man-made horrors.

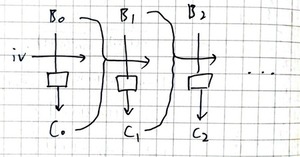

The encrypt() function works by breaking the plaintext pt into blocks $B_0\ B_1\ \cdots\ B_n$ of 16 bytes, and computing the ciphered blocks

$$\begin{align}\label{eq:1} \begin{split} C_0 &= f(B_0\oplus\text{iv}), \\ C_1 &= f(B_1\oplus B_0\oplus C_0), \\ C_2 &= f(B_2\oplus B_1\oplus C_1), \\ &\;\;\vdots \end{split} \end{align}$$

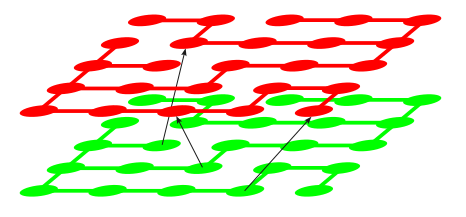

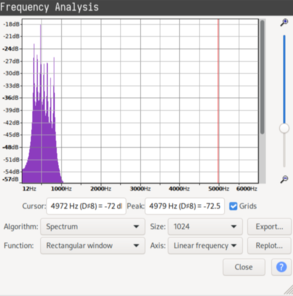

Here $f$ refers to AES encryption of a single block. I usually require pictures to comprehend things, so I turned the equations into a diagram:

|

Figure 1. I thought this looked like ChatGPT attempting to implement AES-CBC, but turns out this is PCBC mode |

On the other hand, decrypt() recovers the plaintext from the ciphertext ct $= C_0\ C_1\ \cdots\ C_n$:

$$\begin{align}\label{eq:2} \begin{split} B_0 &= f\inv(C_0)\oplus\text{iv}, \\ B_1 &= f\inv(C_1)\oplus B_0\oplus C_0, \\ B_2 &= f\inv(C_2)\oplus B_1\oplus C_1, \\ &\;\;\vdots \end{split} \end{align}$$

:

cipher = AES.new(key=key, mode=AES.MODE_ECB)

blocks = [ct[i:i+BLOCK_SIZE] for i in range(0, len(ct), BLOCK_SIZE)]

for block in blocks:

if block in secret_enc:

blocks.remove(block)

[actual decryption code]</code></pre>

The author's intention is probably that we shouldn't obtain the secret by... running the encrypted secret through the decrypt function. To hammer home the point, the author even specifically disallows the entire encrypted secret as input:

res = input("> ")

try:

enc = bytes.fromhex(res)

if (enc == secret_enc):

print("Nice try.")

continue

...

except Exception as e:

print(e)

Nevertheless, a Python programmer would know this is bad code, because it is modifying the list blocks while iterating through it.

To illustrate why, let's iterate through an example list [a,b,c,d], where the bold elements are to be removed. In the first iteration, the current element is at the one at index 0, namely a. It is removed and we proceed to the next iteration. Now the current element is the one at index 1. But because the list is now [b,c,d], the current element is c, meaning we skipped over b! Nevertheless we carry on by removing c and proceeding to the next iteration. Now the current element is the one at index 2. But the list now has only two elements [b,d], and Python silently exits the loop. Notice how b and d were never iterated through.

We can exploit this bug to our advantage. If $A\ B\ C\ \cdots$ are the blocks of the encrypted secret and we input $A\ A\ B\ B\ C\ C\ \cdots$, then the loop will run in such a way that afterwards blocks is [A,B,C,...]. Then the output will be the original secret!

Encrypted secret: aac7f4df9b1bc17b0a6cf8b05eee6f91df947448067a81d6d842bab2995818358aa565e877770e654cf160976159825bffa4fac94e9e9a755bcdf950e369b16fe024964804a863184f089c2a982f1cb2

Enter messages to decrypt (in hex):

> aac7f4df9b1bc17b0a6cf8b05eee6f91aac7f4df9b1bc17b0a6cf8b05eee6f91df947448067a81d6d842bab299581835df947448067a81d6d842bab2995818358aa565e877770e654cf160976159825b8aa565e877770e654cf160976159825bffa4fac94e9e9a755bcdf950e369b16fffa4fac94e9e9a755bcdf950e369b16fe024964804a863184f089c2a982f1cb2e024964804a863184f089c2a982f1cb2

Wow! Here's the flag: grey{00ps_n3v3r_m0d1fy_wh1l3_1t3r4t1ng}

As a small addendum, here's how I would patch the decrypt() function:

def decrypt(ct):

cipher = AES.new(key=key, mode=AES.MODE_ECB)

blocks = [ct[i:i+BLOCK_SIZE] for i in range(0, len(ct), BLOCK_SIZE)]

tmp = iv

ret = b""

for block in blocks:

if block in secret_enc:

continue

res = xor(cipher.decrypt(block), tmp)

ret += res

tmp = xor(block, res)

return ret

Maybe this will work? (code)

As a sequel to the previous challenge, this is more involved. There are two ciphers $C$ and $C^+$. $C$ is the custom one used previously, except for a small change in the decrypt() functionality. $C^+$ is a normal AES-CBC cipher used to encrypt the flag. We have the ciphertext and iv for $C^+$, and its key is the md5 hash of the plaintext secret. Thus the challenge boils down to decrypting the encrypted secret, with which decrypting $C^+$ is trivial.

The decrypt() function is similar to before, except there is no more buggy loop and it filters out any plaintext block appearing in the secret from the return value. Thus the strategy of spitting the encrypted secret $C_0\ C_1\ \cdots\,$ back at the program doesn't work.

My next strategy is to input something of the form $K\ C_0\ C_1\ C_2\ \cdots$, where $K$ is some block. The idea is to pretend the decryption still starts at $C_0$, except through $K$ we have some control over the 'iv' (which is actually $K\oplus f\inv(K)\oplus\text{original iv}$).

To me the most natural value for $K$ is the zero block $\bf0 = 00\ldots00$, because XORing with a zero block does nothing. Then the 'iv' is $D\oplus\text{iv}$ where $D=f\inv(\bf0)$, and using \eqref{eq:1} the decrypted blocks are

$$\begin{align*} \begin{split} &f\inv(C_0)\oplus D\oplus\text{iv} = B_0\oplus D, \\ &f\inv(C_1)\oplus C_0\oplus (B_0\oplus D) = B_1\oplus D, \\ &f\inv(C_2)\oplus C_1\oplus (B_1\oplus D) = B_2\oplus D, \\ &\qquad\qquad\qquad\vdots \end{split} \end{align*}$$

Luckily, these blocks won't be filtered out of the result of decrypt(). So it remains to find $D$, which is equivalent to finding the iv since we know the 'fake iv' $D\oplus\text{iv}$ (it is the first block of the output). I had to play around a bit before figuring out how: we enter the input $\bf0\ \bf0$. Then the equations show that

$$\begin{align*} \bf0 \quad&\text{decrypts to}\quad D\oplus\text{iv}, \\ \bf0 \quad&\text{decrypts to}\quad D\oplus [\bf0\oplus (D\oplus\text{iv})] = \text{iv} \end{align*}$$

Putting all of these steps together:

Encrypted secret: af4ae3bfba4943afc6cd89ec1f39d1cc1a4780b2a7284ca222016bcfdb164b1410c085bda95069f9806b6617ec51e9f447afd84d9e895ffeeda55981ba8b921a600327b6b94ccf8bde0f82a48b6654e4

iv: 6c7d86b1885dfb11314d386aa258d731

ct: 2d8fe378029215028acd66202f5a9e40fdeecd78f5a82af4ac056fdce7201473b906311f2ee3c435094341659e4468b5

Enter messages to decrypt (in hex):

> 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

43d10397330ef5541680cb49ea07a42ac7790c149484952d56bca2a6966b5720

{D+iv = 43d10397330ef5541680cb49ea07a42a, iv = c7790c149484952d56bca2a6966b5720}

> 00000000000000000000000000000000af4ae3bfba4943afc6cd89ec1f39d1cc1a4780b2a7284ca222016bcfdb164b1410c085bda95069f9806b6617ec51e9f447afd84d9e895ffeeda55981ba8b921a600327b6b94ccf8bde0f82a48b6654e4

43d10397330ef5541680cb49ea07a42ac40c7100c3be1a8d58c66a0b5a2c52baccb02b37f21916a74838e1e95830f624299e0aa1458cf1f3eef45eb76a59715002efd5add1741b4f29d0fa18d9eb666d58932658748d4978e277e910be0c2fdd

{block1+D = 43d10397330ef5541680cb49ea07a42a,

block2+D = c40c7100c3be1a8d58c66a0b5a2c52ba,

...}

The secret is therefore

40a47e8364347af418fa03e42640a1b0481824b4559376de08048806245c052ead360522e206918aaec837581635825a8647da2e76fe7b3669ec93f7a5879567dc3b29dbd3072901a24b80ffc260dcd7

and we use its md5 hash along with the given iv to initialize an AES-CBC cipher and decrypt ct.

grey{pcbc_d3crypt10n_0r4cl3_3p1c_f41l}

To obtain the flag, we need to enter the correct password by decrypting the given ciphertext $c_p$. The password is encrypted using a custom implementation of AES, and we are given a 4096-byte (= 256-block) encryption oracle.

In aes.py there is a link to the original implementation. This is useful because we can simply compare the two files to see where changes were made. In this case, the change is in mix_single_column():

Original:

def mix_single_column(a):

# see Sec 4.1.2 in The Design of Rijndael

t = a[0] ^ a[1] ^ a[2] ^ a[3]

u = a[0]

a[0] ^= t ^ xtime(a[0] ^ a[1])

a[1] ^= t ^ xtime(a[1] ^ a[2])

a[2] ^= t ^ xtime(a[2] ^ a[3])

a[3] ^= t ^ xtime(a[3] ^ u)New:

def mix_single_column(a):

a[0], a[1], a[2], a[3] = a[1], a[2], a[3], a[0]To understand how this changes the behaviour of our custom AES, we need to recall the steps involved in encrypting a 16-byte block. I'll let the code list them out for us:

def encrypt_block(self, plaintext):

assert len(plaintext) == 16

plain_state = bytes2matrix(plaintext)

add_round_key(plain_state, self._key_matrices[0])

for i in range(1, self.n_rounds):

sub_bytes(plain_state)

shift_rows(plain_state)

mix_columns(plain_state)

add_round_key(plain_state, self._key_matrices[i])

sub_bytes(plain_state)

shift_rows(plain_state)

add_round_key(plain_state, self._key_matrices[-1])

return matrix2bytes(plain_state)We can see that 4 operations are repeatedly applied to plain_state, starting with add_round_key. To understand their overall effect, it helps to think in abstract terms. This is done by identifying the essential property of each operation, without burying ourselves in its gory details. Let's do it!

I'll treat plain_state as a flat 16-byte block $b_1 \cdots b_{16}$ rather than a matrix, making notation easier. The first operation, add_round_key, XORs each byte $b_i$ with some other byte. (We can ignore where this other byte comes from, and this is an instance of abstraction.) XORing can be thought of as a byte substitution (again abstracting), so we are essentially applying 16 different substitutions, one for each position in the block. In notation, we can say that

$$b_1 \cdots b_{16} \quad\text{maps to}\quad f_1(b_1) \cdots f_{16}(b_{16}),$$

where the $f_i$'s are substitutions. In fact, the next operation sub_bytes has the same effect on the block (we are now in the for loop), so the result after add_round_key then sub_bytes is also in the form $f_1(b_1) \cdots f_{16}(b_{16})$!

The next operation is shift_rows, which essentially rearranges the bytes within the block. So the block now has the form

$$\begin{equation}\label{eq:3}f_{\tau(1)}(b_{\tau(1)}) \cdots f_{\tau(16)}(b_{\tau(16)}),\end{equation}$$

where $\tau$ is a permutation of $\{1,\ldots,16\}$. Here we arrive at the crux of the challenge with mix_columns. In the original implementation, this operation is a rather complicated one that cannot be expressed as a substitution or a rearrangement, and our abstractions would be insufficient. But now, mix_columns turns out to be yet another rearrangement, so the block ends up with the same form \eqref{eq:3}. In fact it remains so after another add_round_key, thus completing one round.

This form is so important we should give it a name: a twisted substitution. Thus we have shown that one round of encryption gives us a twisted substitution. It shouldn't be too hard to see that 10 rounds (and the remaining operations thereafter) also results in a twisted substitution. This is big. A twisted substitution means that each byte of the input block affects only one byte of the output; let's call it the partner byte (I really like making up names). To illustrate, if for example the first byte $b_1$ was changed to $c_1$, then the output has the form

$$f_{\tau(1)}(b_{\tau(1)}) \cdots f_{\tau(i)}(c_{\tau(i)}) \cdots f_{\tau(16)}(b_{\tau(16)}),$$

where $i$ is sent to 1. This differs from $f_{\tau(1)}(b_\tau(1)) \cdots f_{\tau(16)}(b_{\tau(16)})$ by only one byte!

To crack the encryption, we therefore need to determine the partner bytes as well as the 16 substitutions. The former can be determined by running the AES implementation locally on judiciously chosen blocks, and the latter can be determined by sending the series of blocks

$$0\ 0\ \cdots\ 0,\quad 1\ 1\ \cdots\ 1, \quad\text{up to}\quad 255\ 255\ \cdots 255.$$

Using the encrypted output, we can determine how every possible value in each byte is substituted in the partner byte, and that allows us to decrypt the ciphertext and obtain the flag.

My actual solution was slightly funky. It had completely escaped me that the partner bytes could be determined beforehand, so I was fixated on determining that and the substitutions in my 256-block payload. I came up with the following:

0 0 0 0 ... 0 0

0 1 1 1 ... 1 1

1 1 2 2 ... 2 2

2 2 2 3 ... 3 3

3 3 3 3 ... 4 4

...

14 14 14 14 ... 14 15

15 15 15 15 ... 15 15

16 16 16 16 ... 16 16

...

254 254 254 254 ... 254 254

From the first to the second block, the first byte is fixed while all others are incremented. Then the second byte is fixed while all others are incremented, and so on. This goes on until the 17th block, and thereafter all bytes are incremented normally. We can determine the partner bytes within the first 17 blocks, by checking which output byte remains fixed from one input block to the next. Also note that I can only go up to 254 due to the block limit, but this isn't an issue because the plaintext shouldn't contain '255' bytes anyway.

Finally here's my implementation:

from pwn import *

# Builds the payload as described above

payload = b''

# First block

block = [0 for _ in range(16)]

payload += bytes(block)

for k in range(16): # Next 16 blocks

for i in range(16):

if i != k: block[i] += 1

payload += bytes(block)

for k in range(16,255): # Rest of the blocks

payload += bytes([k for _ in range(16)])

# Initiate connection ---------------------------

r = remote('challs.nusgreyhats.org', 35100)

r.recvuntil(b': ')

r.send(payload.hex().encode() + b'\n')

r.recvuntil(b'c: ')

c = bytes.fromhex(r.recvline().decode()[:-33])

r.recvuntil(b'c_p: ')

cp = bytes.fromhex(r.recvline().decode()[:-33])

# Chunk output into blocks

blocks = []

for i in range(0,len(c),16):

blocks.append(c[i:i+16])

# Determine partner bytes (and its inverse)

partners = []

for i in range(16):

partners.append(xor(blocks[i], blocks[i+1]).find(b'\x00'))

inverse_partners = []

for i in range(16):

inverse_partners.append(partners.index(i))

print(partners, inverse_partners)

# Crack the encrypted password!

pw = [None for _ in range(16)]

for i in range(16):

for idx, block in enumerate(blocks):

if block[i] == cp[i]:

pw[inverse_partners[i]] = int(payload[idx*16+inverse_partners[i]])

r.send(bytes(pw).hex().encode() + b'\n')

# Program will print out the flag

r.interactive()[+] Opening connection to challs.nusgreyhats.org on port 35100: Done

[7, 12, 5, 14, 11, 0, 9, 2, 15, 4, 13, 6, 3, 8, 1, 10] [5, 14, 7, 12, 9, 2, 11, 0, 13, 6, 15, 4, 1, 10, 3, 8]

[*] Switching to interactive mode

password: flag: grey{mix_column_is_important_in_AES_ExB3Hf9q9I3m}

The challenge is to distinguish between a true RNG and a fake RNG. We have to be correct 100 times in a row, so clearly blind guessing won't work. We'd have to figure out how this fake RNG really works.

Firstly, $x$, $r$ and $k$ are randomly initialized as length 64 bit-strings, which can be thought of as elements of $\F_2^{64}$. Then $x$ is repeatedly updated $16\cdot8$ times according to the rule

$$x\mapsto\begin{cases} Ax+r,&i\equiv0\pmod3 \\ Ax+k,&i\equiv1\pmod3 \\ Ax+r+k,&i\equiv2\pmod3, \\ \end{cases}$$

where all operations are carried out over $\F_2$. The components within the iterates of $x$ are summed up mod 2, and the sums (which are bits) are concatenated to form 16 bytes; this is our custom random value.

Given a vector $v=(v_1,\dots,v_{64})\in\F_2^{64}$, we can define $s(v)=\sum_i v_i$, and so the output bits $b_1,\ldots,b_{128}$ satisfy the equations

$$\begin{align}\label{eq:4} \begin{split} s(x) &= b_1 \\ s(Ax+r) &= b_2 \\ s\bigl(A(Ax+r)+k\bigr) &= b_3 \\ &\vdots \end{split} \end{align}$$

Crucially, each LHS can be expressed as a linear combination of variables

$$x_1,\ldots,x_{64},r_1,\ldots,r_{64},k_1,\ldots,k_{64},$$

where $x=(x_i)$, $r=(r_i)$ and $k=(k_i)$. Therefore, the question of whether a given output $b_1,\ldots,b_{128}$ is customly generated boils down to determining whether the linear system \eqref{eq:4} is solvable in the $x_i$'s, $r_i$'s and $k_i$'s. It is a system of $128$ equations with $192$ unknowns, which is still pretty manageable for Sage.

from pwn import *

from sage.all import *

A = [omitted] # From param.py

# Build matrix corresponding to the system of linear equations -----------

F = GF(2)

# A linear combination of x_i's, r_i's and k_i's is represented by a length 64*3=192 vector

# X(i) generates the vector for the linear combination x_i

# R(i) generates the vector for the linear combination k_i

# K(i) generates the vector for the linear combination k_i

def X(i): return vector(F, [0 for _ in range(i)] + [1] + [0 for _ in range(3*64-i-1)])

def R(i): return vector(F, [0 for _ in range(64+i)] + [1] + [0 for _ in range(2*64-i-1)])

def K(i): return vector(F, [0 for _ in range(2*64+i)] + [1] + [0 for _ in range(64-i-1)])

Z = vector(F, [0 for _ in range(3*64)]) # Zero vector

M = []

vs = []

for i in range(64):

v = vector(F, X(i))

vs.append(v)

M.append(sum(vs))

for n in range(16*8-1):

if n%3 == 0: RK = R

elif n%3 == 1: RK = K

else: RK = lambda i: R(i)+K(i)

new_vs = []

for i in range(64):

new_v = RK(i)

for j in range(64):

new_v += A[i][j] * vs[j]

new_vs.append(new_v)

M.append(sum(new_vs))

vs = new_vs

M = Matrix(F, M)

# Initiate the connection ------------------------------------------------

def bytes_to_bits(s):

return list(map(int, ''.join(format(x, '08b') for x in s)))

def bits_to_bytes(b):

return bytes(int(''.join(map(str, b[i:i+8])), 2) for i in range(0, len(b), 8))

r = remote('challs.nusgreyhats.org', 35101)

r.recvuntil(b'Output: ')

for i in range(100):

L = r.recvline()

print(L)

v = vector(F, bytes_to_bits(bytes.fromhex(L[:-1].decode())))

try:

M.solve_right(v)

result = b'1\n'

except:

result = b'0\n'

r.send(result)

print(result)

if i < 99:

r.recvuntil(b'Output: ')

else:

print(r.recvline())[+] Opening connection to challs.nusgreyhats.org on port 35101: Done

b'4ce524904e54ee6b1d8679c09a6d3d5f\n'

b'1\n'

b'293b926e01d734dd23ce68e57eae167a\n'

b'1\n'

b'e26d207b2293366a0e5af8c1c604361c\n'

b'0\n'

...

b"What's your guess? (0/1): Congrats! Here is your flag: grey{Not_so_easy_to_construct_a_secure_PRG_LaQSqprzmTjBZs8ygMkGuw}\n"Fun fact: the hardest part of this challenge was getting pwntools and sage working together, because I didn't setup my Python environments properly. This is a good learning lesson.

I want to count from 0

The distribution provided came with the following files:

.:

docker-compose.yml Dockerfile expected_output.txt run.py run.sh test

./test:

file_list.txt testbench.v test.shAt this point I was in the same position as fellow participant PotatoCider (see their writeup here): with essentially zero knowledge of Verilog. But that isn't going to stop me, because sometimes in a CTF you have to pick up things on the fly.

The first thing I looked out for was the main entry point, which seemed to be run.py and run.sh. run.sh simply runs the py version so it's redundant. run.py asks the user to input base64-encoded Verilog code, decodes it, filters out a list of 'bad words' (namely if, else, ? and +), and then runs it... somehow (for some reason I didn't read through that portion of the code at the time).

Outside of run.py, the file expected_output.txt caught my eye. Clearly, we are supposed to write some Verilog code that produces the following output:

clk 0, result 0

clk 1, result 1

clk 0, result 1

clk 1, result 2

clk 0, result 2

...

clk 1, result 65537

clk 0, result 65537

clk 1, result 65538

clk 0, result 65538I also peeked into the test directory to see what was up. It took me a bit to figure out, but I realised its purpose was to test our solution locally. We have to put our solution in solve.v (as indicated in file_list.txt), and then ./test.sh will produce an output like the one above. After I perfected my solve.v, then I could base64-encode it and send it to the server for real. Since I wasn't familiar with Verilog, I figured I should first get some working solution even it contained bad words, and only then focus on eliminating the bad words.

This was a perfect opportunity to apply the newfangled technique of prompt engineering:

|

Figure 2. Dramatic reenactment. My actual prompts were a lot messier |

The code I was asking ChatGPT to use was from testbench.v. I added it so that the code produced would interface with testbench.v properly. Its first output was this:

module counter (

input wire clk,

output reg [31:0] result

);

reg [16:0] count;

always @(posedge clk) begin

if (count == 0 || count == 1 || count == 65537 || count == 65538) begin

result <= count;

end

count <= (count == 65538) ? 0 : count + 1;

end

endmoduleThe corresponding output is this:

clk 0, result x

clk 1, result x

clk 0, result x

clk 1, result x

...Even though we have these mysterious x's, I consider this a minor success! The fact that there was some output means our code had the correct syntax, so we can focus on the implementation of the counter. Through more prompting I found out the x's were because result wasn't initialized at the start.

I (or rather ChatGPT) eventually managed to simplify the horrendously complicated code in the beginning to this:

module counter (

input wire clk,

output reg [31:0] result

);

initial begin

result = 0;

end

always @(posedge clk) begin

result <= result + 1;

end

endmoduleIt does give the expected output! But there is a + which isn't allowed. How was I going to replicate the effect of an increment without an addition sign?

I noticed the - sign was allowed, and a light bulb went off in my head. Maybe I could subtract from result a number so huge, it causes an overflow. And we need to overflow by an exact number, so as to produce the effect of adding by 1. Of course, I ask ChatGPT to compute that number for me:

|

Figure 3. Had to sneak in the word 'overflow' to hint the AI of my devious intentions |

It was actually off by 1, the actual number being 4294967295. So this was my perfected solve.v:

module counter (

input wire clk,

output reg [31:0] result

);

initial begin

result = 0;

end

always @(posedge clk) begin

result <= result - 4294967295;

end

endmodule$ nc challs.nusgreyhats.org 31114

base64 encoded input: bW9kdWxlIGNvdW50ZXIgKAogICAgaW5wdXQgd2lyZSBjbGssCiAgICBvdXRwdXQgcmVnIFszMTowXSByZXN1bHQKKTsKCmluaXRpYWwgYmVnaW4KICAgcmVzdWx0ID0gMDsKZW5kCgphbHdheXMgQChwb3NlZGdlIGNsaykgYmVnaW4KICAgcmVzdWx0IDw9IHJlc3VsdCAtIDQyOTQ5NjcyOTU7CmVuZAoKZW5kbW9kdWxl

Received Verilog code!

Congratulations! Flag: grey{c0un71n6_w17h_r1pp13_4ddr5}Ripple adder? What's that?

The maze trials were just the start. As a master of mazes, you find yourself still confined in a maze. At least you've got some superpowers this time... nc challs.nusgreyhats.org 31112

Connecting to that port, we are greeted with this:

LEVEL 1:

┏━━━━━━━┳━━━━━━━━━━━┓

┃ ┃ ┃

┣━━━┓ ┗━━━━━━━ ┃

┃ ┃ ┃

┃ ┗━━━┳━━━━━━━ ┃

┃ ┃ ┃

┃ ━━━━┛ ┏━━━━━━━┫

┃ ┃ ┃

┃ ━━━━━━━━┛ ╻ ┃

┃ ┃ ┃

┗━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━┻━━━┛

You have been given 1 wall-phases

Hurry! How many steps does it take to escape?

█

We have to find the shortest path from the upper-left to the lower-right corner, taking into account the wall-phasing powerup. If we answer wrongly or take too long we are kicked out. If we answer correctly before the timeout, we advance to the next level with a bigger maze. This continues for many many levels (50, it turns out) and the mazes get very very big, so this challenge is clearly not designed for manual solving. We'd have to write a script to automatically solve the mazes.

The standard technique for finding shortest paths in mazes is to convert the maze into a graph $G$ where nodes correspond to the grid positions in the maze, and two adjacent (vertically or horizontally) nodes are connected by an edge both ways, if they are not separated by a wall. Then we use Djikstra to find the shortest path between the corners of this graph.

|

Figure 4. The maze above converted to a graph |

However, the wall-phases mean we can't directly adopt this approach. After some research I found this very elegant solution. The suggested answer tells us to form a graph $G^+$ as $k+1$ copies (or 'levels') of $G$, where $k$ is the number of allowed wall-phases. Each node of $G^+$ has the form $(p,y)$ where $p$ is a node in $G$ and $y$ is the level. For each level $y$, we have edges between $(p,y)$ and $(q,y)$ if $p$ and $q$ have an edge in $G$. But additionally, we have an edge from $(p,y)$ to $(q,y+1)$ (as well as from $(q,y)$ to $(p,y+1)$) if $p$ and $q$ are separated by a wall. (The exception is when $y$ is the top level, in which case there are no edges going out to other levels.)

|

Figure 5. Some examples of edges across levels (sorry for the horrible-looking diagram) |

We can see that this graph is "correct", because every path in the maze (taking into account wall-phases) corresponds to a unique path in the graph, and vice versa. Finally, we use Djikstra to find the shortest distance from the top-left corner on the bottom level, to the bottom-right corner on any level. What this means is that for each $0\le i\le k$, we are finding the shortest distance using exactly $i$ wall-phases, and then we find the minimum of all these shortest distances, which is our answer. These ideas are implemented below:

import heapq

from pwn import *

left = 0

right = 1

up = 2

down = 3

# From ChatGPT

def shortest_distance(graph, start, targets):

distances = {node: float('inf') for node in graph}

distances[start] = 0

priority_queue = [(0, start)]

while priority_queue:

current_distance, current_node = heapq.heappop(priority_queue)

if current_distance > distances[current_node]:

continue

for neighbor in graph[current_node]:

distance = current_distance + 1

if distance < distances[neighbor]:

distances[neighbor] = distance

heapq.heappush(priority_queue, (distance, neighbor))

return min(distances[target] for target in targets)

# M is an NxN matrix of sublists of [0,1,2,3] (left, right, up, down)

# k is how many walls can be phased through

def build_graph(M, n):

h = len(M)

w = len(M[0])

D = dict()

for i in range(h):

for j in range(w):

for k in range(n+1):

L = []

if left in M[i][j]: L.append((i,j-1,k))

elif k < n and j > 0: L.append((i,j-1,k+1))

if right in M[i][j]: L.append((i,j+1,k))

elif k < n and j < w-1: L.append((i,j+1,k+1))

if up in M[i][j]: L.append((i-1,j,k))

elif k < n and i > 0: L.append((i-1,j,k+1))

if down in M[i][j]: L.append((i+1,j,k))

elif k < n and i < h-1: L.append((i+1,j,k+1))

D.update({(i,j,k): L})

return D

def parse_maze(s):

s = [line.strip() for line in s.split('\n') if line != '']

n = len(s[0])

w = (len(s[0])-1)//4

h = (len(s)-1)//2

M = [[[0,1,2,3] for _ in range(w)] for __ in range(h)]

for i in range(h):

for j in range(w):

I, J = 1+2*i, 2+4*j

if j == 0 or s[I][J-2] == '┃': M[i][j].remove(left)

if j == w-1 or s[I][J+2] == '┃': M[i][j].remove(right)

if i == 0 or s[I-1][J] == '━': M[i][j].remove(up)

if i == h-1 or s[I+1][J] == '━': M[i][j].remove(down)

return M,w,h

r = remote('challs.nusgreyhats.org', 31112)

while True:

r.recvuntil(b'LEVEL ')

s = int(r.recvuntil(b':',drop=True).decode())

print(s)

r.recvline()

maze = r.recvuntil(b'You have been given ', drop=True).decode()

n = int(r.recvuntil(b' '))

r.recvuntil(b'escape?')

maze, w, h = parse_maze(maze)

G = build_graph(maze, n)

k = str(shortest_distance(G, (0,0,0), [(h-1,w-1,k) for k in range(n+1)]))

r.send(k.encode() + b'\n')

if s == 50:

r.interactive()

break[+] Opening connection to challs.nusgreyhats.org on port 31112: Done

1

2

3

...

48

49

50

[*] Switching to interactive mode

--------------------------------------------------

Congratulations! You've made it out of the maze! Your determination, courage, and problem-solving skills have led you to freedom. Now, embrace the next chapter of your journey with the same resilience and bravery. The maze may be behind you, but the adventure continues!

grey{g1ad3rs_pha5erS_y0u_hAvE_jo1n3d_tH3_m4ze_eSc4p3rs!}What kind of music is this? Warning: Audio file may be loud! (.zip distribution)

The zip distribution contained the following files:

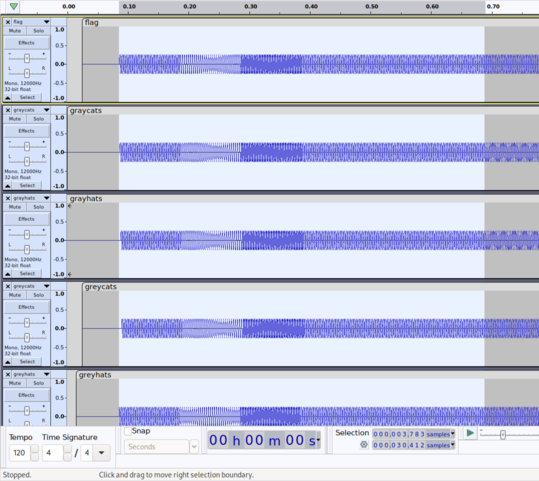

flag.flac graycats.flac grayhats.flac greycats.flac greyhats.flac.flac is an audio format like .wav and .mp3, often used in CDs. The first thing I do with an audio file is open it in Audacity. Audacity lets you observe the raw waveform which sometimes offers helpful clues.

|

Figure 6. After importing all .flacs |

The first clue is that each audio file is divided into many tiny chunks; this can be confirmed by playing them back and hearing a sequence of distinct tones. Furthermore, the first few chunks are the same across all files! This certainly can't be a coincidence.

|

Figure 7. Notice how the first few chunks are all the same |

I then noticed another important clue: the filenames. I made an educated guess that the audio data was encoding the filename, which was supported by two things. First, the flag audio lasts for much longer than the others, which is reasonable since the flag itself is likely much longer than the 8 characters of g(r|e)y(c|h)ats. Second, the first two characters of each filename are the same (note the flag has the form grey{...}), which explains the matching chunks observed earlier. Acting on this guess, it remains to determine the coding scheme.

We know that the filenames differ from the third character onwards. From a straightforward visual inspection, it can also be seen that the chunks differ from the seventh one onwards. Thus I inferred that each character is coded by a triplet of chunks.

|

Figure 8. The first 6 chunks match |

Next was to determine how many unique frequencies there were for the chunks. The plan is that afterwards we could label these frequencies, and populate a lookup table using the known characters and their respective codes. Then we look for patterns that let us determine the chunk triplet coding any character, which allows us to decode flag.flac.

There are multiple ways of determining the number of frequencies: one could rely on visual inspection, or slow down the file a lot and do aural inspection to isolate the individual pitches, or write a script. But the easiest way is actually to plot the spectrum of the entire file (in Audacity this is under the Analyze toolbar).

|

Figure 9. I swear when I was solving it there wasn't such a long tail. But whatever |

Recall that any waveform can be decomposed into sine waves of different frequencies, and the spectrum plot tells us the amplitude of each frequency. Since the given audio files consist of a sequence of sine wave chunks, one would expect their amplitudes would be greatest for the frequencies in the chunks. The plot supports this, showing 7 distinct peaks which mean there are 7 different frequencies. It is reasonable to label these with digits 0 to 6, in increasing order of frequency.

We can then see that the following characters are coded by the given triplet of digits:

$$\begin{align*} \text g&\mapsto205,\ \text r\mapsto 222,\ \text a\mapsto 166,\ \text e\mapsto 203,\ \text y\mapsto 232, \\ \text h&\mapsto206,\ \text c\mapsto 201,\ \text t\mapsto 224,\ \text s\mapsto 223. \end{align*}$$

To me it is quite clear that the triplets are meant to interpreted as base 7 numbers of some kind. This is because g and h are adjacent letters and they have adjacent codes, and indeed c=201 is two more than a=166. The most obvious possibility is that the base 7 numbers represent ASCII codes, which they do! With this knowledge, it remains to decode flag.flac.

I did it manually which was a painstaking process and rather error-prone. Basically I would select each triplet of chunks one-by-one, and then use the spectrum plot to determine their frequencies. In hindsight a Python script might have saved some time, but it doesn't matter as I got the flag in the end.

|

Figure 10. My awfully messy working in decoding the flag |

grey{why_th3_7f3k_fr3qu3ncy_sh1ft_0349jf0erjf9jdsgdfg}